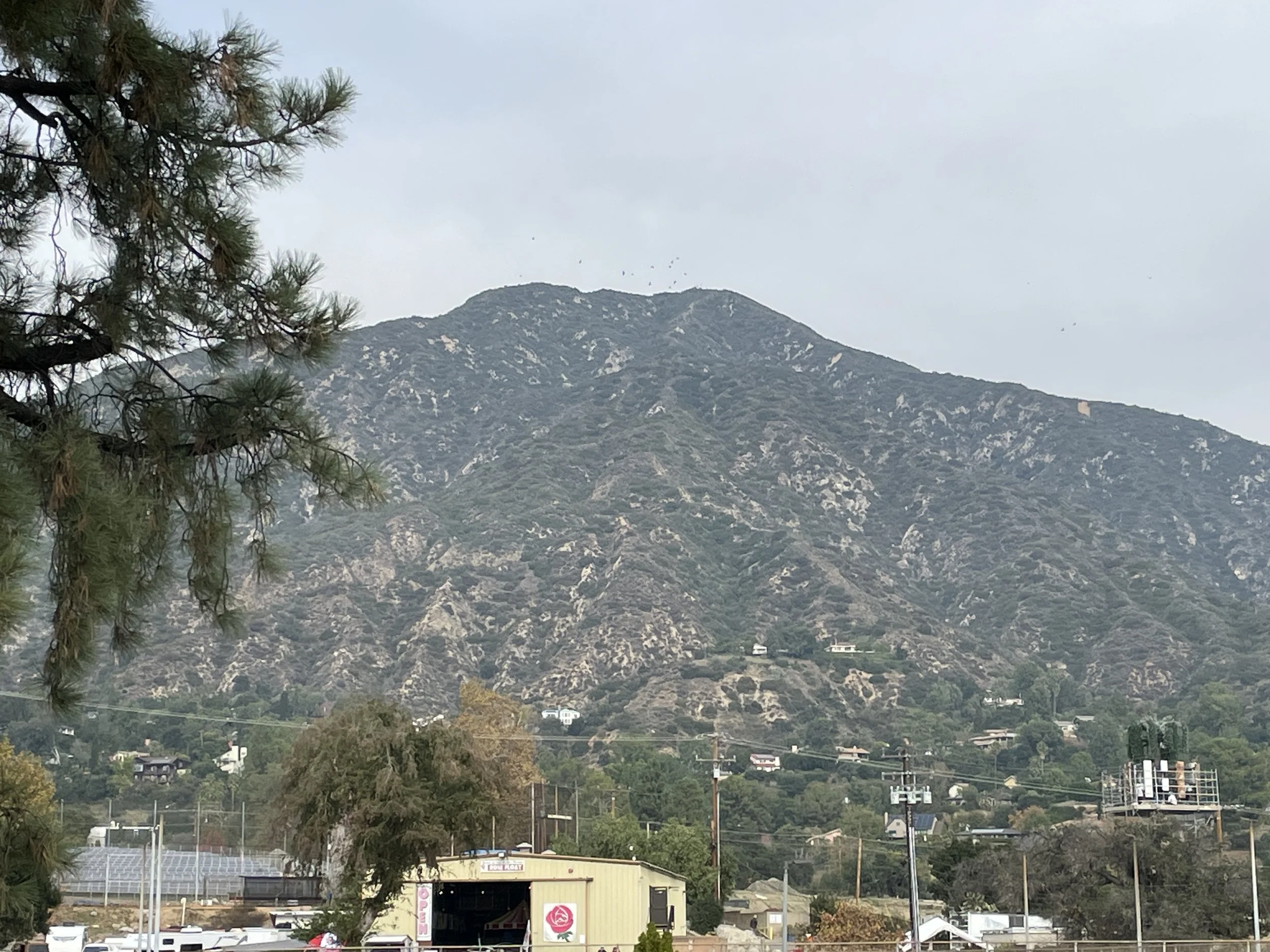

Today I took the dogs on a longer walk, one that winds through a small cemetery. It’s a beautiful spot, one that looks up toward the majesty of the San Gabriel Mountains. As I walked through, I read the dates on the tombstones. One was for a man who was called a “pioneer,” having been born in 1850, the same year California became a state. Another read “age 33,” but no date of death, and still another was for a girl named Cindy born in 1977, fifteen years after I was born. Cindy died at age 9 in 1986, the year I got married.

As the dogs and I trekked through the cemetery, I thought about dying at 9 or 33 or 55. While a short life seems sad, it also occurs to me that it doesn’t permit the personal growth, change, or transformation that growing older (and dying older) allows. While we can see aging as wrinkles and a loss of youthful bodies that could move freely without pain, growing older offers us that chance to move beyond the limiting beliefs we absorb when we’re younger. When I was 9, I couldn’t cognitively understand how to manage fear and worry, and as a teen, I didn’t know how little others’ opinions about me or what I chose to do really mattered. At 33, I didn’t know that my job or the lack of a career didn’t define my value as a human being, and at 55, I didn’t know that despite not having the certainty how things would turn out, I would be OK regardless. We celebrate long life because it allows us to experience the delight and wonder of being human, but a long life also should be celebrated if it has brought personal change through a broadened and inclusive perspective, more patience with others and fewer sharp edges in our interactions, and an abiding sense of our worthiness just to be alive.